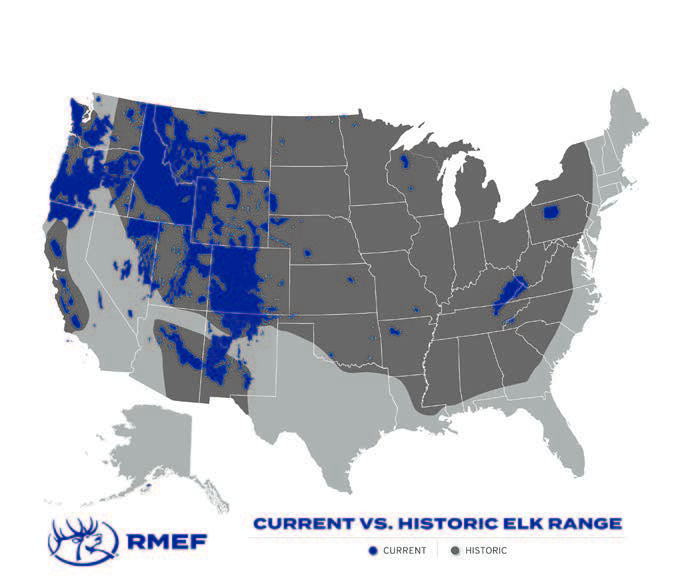

Elk are an iconic antlered animal typically identified with the rugged western mountains. While that’s true today, historically elk roamed across most of the United States, including the Great Plains and the eastern forests.

Eastern elk populations peaked in the 1600s. Two centuries later, the eastern subspecies was extinct due to overhunting. European settlers and Native Americans sought these large animals, which could weigh over 800 pounds, for their mild meat. What’s more, jewelers adorned watch fobs with elk ivories (the two molars elk use to grind up grasses and nuts). Market hunters slaughtered innumerable elk simply for their ivories. By the late 1800s, elk survived only in the most remote parts of the Rocky Mountains and other western mountain ranges.

In 1872, with the establishment of Yellowstone National Park, elk got a much-needed safety zone. Other western national parks and the National Elk Refuge in Wyoming gave further protection to the remaining elk. In 1925, the Izaak Walton League bought 1,760 acres of private land in Wyoming to expand that refuge to 3,520 acres and donated more land in 1927.

Today, Colorado has the largest herd in the United States, about 300,000 animals. Elk in Montana, Oregon, Idaho and Wyoming number between 100,000 and 150,000. New Mexico, Utah and Washington have 50,000 to 80,000 elk, and Arizona, Nevada, California and Kentucky have 10,000 to 25,000 elk. Wait, Kentucky? That’s an eastern state!

Elk Return to Kentucky

Elk and many other native species were extirpated from Kentucky by the 1850s. During the 1970s and 1980s, restoring Kentucky’s wildlife became a priority for the state’s conservation department, but it took another decade before it focused on elk.

“We were done with white-tailed deer, wild turkeys, otters, et cetera, and thought about what should be next,” says Gabe Jenkins, acting director, Information and Education Division, Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources. “Elk were native. Sportsmen and women were happy about it, but we needed to determine where to have them and what their long-term viability was.”

Elk, which are grazers, thrive on these meadows, feeding on the grasses then retreating into the woods for protection and shade. But eventually, the trees try to take over those meadows again.

A feasibility study pointed to three locations in eastern Kentucky. With overwhelming support from people in those areas, the state brought in its first 12 elk in 1997. It continued to import elk from six different western states, 1,559 total animals. Today, its elk herd numbers 13,000 to 14,000. Eastern Kentucky’s elk flourish mainly because it has more elk-friendly habitat, thanks to the coal mining industry.

Kentucky’s coal seams are near the surface on the tops of its mountains, which are naturally forested. When mined, the mountaintops are scraped down to the coal. Afterward, the reclaimed area is planted with grass, which grows better than trees at first because the replacement soil is more compacted than the original forest floor.

“In the 1990s, when coal was booming, we stayed on the green wave of habitat,” says Jenkins. “The challenge now is how to keep those grasslands as grass. Our elk are still doing well. We used to think they had to have lots of grass and big open spaces, but they’re reverting to a traditional eastern herd. Instead of 200 elk together, we’re finding smaller herds on patches of grass.”

Elk, which are grazers, thrive on these meadows, feeding on the grasses then retreating into the woods for protection and shade. But eventually, the trees try to take over those meadows again.

Maintaining grasslands is a challenge voiced by other eastern states where elk have returned. Pennsylvania’s herd, which is older, first introduced in 1913, and smaller, between 1,300 and 1,400 elk, finds grass mainly where timber has been clear cut.

“We introduced elk in the north-central part of the state, where 70 percent of the land is public,” says Jeremy Banfield, wildlife biologist with the Pennsylvania Game Commission. “The elk stay out of trouble. We can’t bulldoze trees and plant grass. Kentucky had the coal industry do it. Plus, our sister agency [the state’s Bureau of Forestry] has an interest in maintaining the timber. We’re probably never going to have tens of thousands of elk.”

Realistically, Kentucky will probably be the only state east of the Mississippi to have such a large elk population in the 21st century because they have the habitat to support it.

In 2002, Tennessee reintroduced elk, which have grown to a population of about 400. It used former coal reclamation areas for its herd, too, but instead of mountaintops, its mines were “strip benches,” on the sides of mountains, which are smaller and thus support fewer elk.

“After seeing the success in Kentucky, we had interest here,” explains Brad Miller, elk program coordinator for the Tennessee Wildlife Resource Agency. “Our elk range butts up against Kentucky’s range. Some were already coming here.”

“We wanted to release elk in western Tennessee, but there were too many potential conflicts with agriculture, so we decided on the Cumberland Mountains where there’s minimal row crops, large amounts of public land and low human density. Our approach is to create as many openings as we can, but we’re limited by topography.”

The Elk Experiment

Few farms, low population and plenty of space are common criteria among all of the states that have reintroduced elk; however, some states don’t have substantial reclamation areas. Instead of looking at Kentucky as a role model, they’ve taken cues from an elk experiment in Great Smoky Mountain National Park (GSMNP).

In 2001, the National Park Service introduced 52 elk into the Cataloochee Valley, an isolated part of GSMNP in North Carolina, to see if they could survive. They did, much to the enjoyment of wildlife watchers. In 2008, the reintroduction of elk to GSMNP was deemed a success. As a result, oversight of elk that left the park transferred to the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Agency (NCWRA) or the Eastern Band of Cherokee Nation, depending on the location. If the elk wandered out of the national park onto the adjacent reservation, the Cherokees managed them, otherwise; they became NCWRA’s responsibility.

According to Justin McVey, district wildlife biologist for NCWRA, by 2012, the elk herd in North Carolina numbered about 150 animals. The park service wanted to bring in more, but chronic wasting disease (CWD) had crossed the Mississippi, and North Carolina placed a moratorium on importing all hoofed mammals.

Elk, like deer and moose, can contract the disease. It’s the risk of infecting elk with CWD that caused eastern states to stop importing elk from other states. Of the eastern states with elk, Kentucky is the only state that does not have CWD in its deer or elk herds. (See “Chronic Wasting Disease: The Evolving Challenge,” Outdoor America, 2018, Issue 2.)

Today, North Carolina has about 200 elk. “With just 52 founding members, it takes a while to grow a herd,” says McVey.

“Our goal is to eventually have a huntable, sustainable population of elk. Western North Carolina, where our elk are, is mature forest. Our elk eat acorns, but how many months of the year are acorns available? They still need to graze…We don’t have lots of open lands, and if we do, it’s typically private…We’re putting a lot of effort into building habitat on public land.”

Wisconsin also decided to reintroduce elk specifically to its forested public lands, first in the northern part of the state and later to its central forests. Not only did Wisconsin lack mine reclamation areas, it had no mountains, a much colder climate and more predators.

“In 1989, we did a feasibility study that looked at bringing back three different native species: elk, moose and woodland caribou,” says Scott Roepke, wildlife biologist with the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. “Elk had the best chance of survival. There’s a lot of timber harvested in Wisconsin. A clearcut provides elk food – grasses, forbs and young woody browse – for 10 years. The timber industry constantly creates a mosaic of forest and openings. We knew elk could do well here because they did historically. We had the habitat and most of it is public.”

Yet, Wisconsin is home to over 1,000 wolves, as well as black bears and bobcats, which gladly prey on young elk calves. In addition, during the winter, temperatures can drop to -30 degrees Fahrenheit. Not exactly productive habitat for elk, but they have survived there since 1995, when the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point got permission to bring 25 elk into the state from Michigan. In 2017 and 2019, the herd was augmented with another 141 elk from Kentucky. Today, there are 300 elk in Wisconsin’s northern herd, plus another 100 in its central herd.

According to Roepke, there are no plans to continue importing more elk into Wisconsin for four reasons: 1. disease concerns, particularly CWD; 2. the time and high cost of transporting them, monitoring them in a holding area and then releasing them; 3. its herds are nearing capacity in the two areas where they are located; and 4. the state wants to slow the growth rate of the herd.

“Elk are new on the landscape,” says Roepke. “We don’t want to overwhelm either the land or the people.”

Elk Versus White-Tailed Deer

While elk and white-tailed deer are admired for their antlers and can share the same habitat, they are very different animals:

- Elk are much bigger, sometimes exceeding 800 pounds. Deer rarely weigh more than 250 pounds.

- Elk are taller, up to five feet at the shoulder, two feet taller than the average white-tailed deer.

- Male elk are called bulls, female elk are cows, and young elk are calves. Deer are known as bucks, does and fawns, respectively.

- Both bull elk and white-tailed bucks have antlers which they shed and regrow annually. However, a mature bull’s rack is bigger, bulkier and sweeps back, whereas a buck’s rack curves forward.

- Both elk calves and white-tailed fawns have spots. Elk typically give birth to only one calf though they might have twins. Whitetails often have twins.

- Elk are known as grazers, and they do eat lots of grass, but they will also feed on forbs, mast (wild nuts like acorns), low-growing plants, berries, tender shoots, twigs, lichen, bark and evergreen needles, depending on the time of year and what’s available. Deer are primarily browsers, preferring forbs, leaves, shoots, buds and mast. They rarely graze.

Elk and Ag Lands

Disease transmission isn’t the only issue when a state contemplates bringing back elk. Harm to agricultural lands is another. Farmers are typically one of the strongest voices against the reintroduction. While every conservation department is sensitive to farmers’ concerns, each one has different ways of dealing with damage, which on the whole has been minimal.

Elk have a reputation for eating and trampling crops and breaking fences, but that has not proven the case in Kentucky mainly because commercial agriculture doesn’t exist in eastern Kentucky where the elk are. “I can think of maybe one cornfield, but people have personal gardens, and many are subsistence gardens,” says Jenkins. “It’s at a manageable level. Sometimes we work with landowners to put up fencing [to keep the elk out].”

In Pennsylvania, farmers are allowed to shoot an elk if they feel it is harming their livelihood. It’s not common, as the elk management area does not have a lot of agricultural land. “The elk don’t damage fences because there aren’t many and they respect electric ones, but they do get into corn on occasion,” says Banfield. “The chief source of damage is residential, similar to white-tailed deer. An elk can eat $10,000 of landscaping overnight!”

North Carolina has a deprivation rule, too, meaning it’s okay to kill an elk if it’s causing damage as long as the landowner contacts the NCWRA within 24 hours. “Sometimes elk knock down old barb wire, and cattle get out. Elk get into gardens, but there isn’t a lot of large agricultural operations where our elk are. Then there’s the folks who love elk and feed them. That’s one more fire to put out…But I’m confident we can have a huntable herd with negligible human interactions and non-consumptive ways to enjoy them,” says McVey.

In Tennessee, a landowner attitudes survey also found limited elk conflicts and, overall, a good attitude among the few farmers in the state’s elk zone. “Elk are in pastures, row crops, eating hay and there’s been some damage to ornamental plantings, but not a lot,” says Brad Miller. “For ag issues, we start with landowner education. Occasionally we use electric fences if it’s a small area like a backyard garden. We aren’t allowed to pay people for elk damage.”

In Wisconsin, where agricultural areas are both within and surrounding its elk management areas, the state can compensate landowners as they would for damage caused by deer and other species. “Shooting is a last resort,” says Roepke. “There’s a lot of public interest in seeing our elk herds grow. Sometimes we trap and move a group of elk, but that only works with a herd, not if there’s only one animal. Compensation is really our main solution.”

Hunting Eastern Elk

For all of the states that have reintroduced elk, having a hunting season has always been part of the plan. In 2001, Kentucky implemented a hunting season while they were still moving elk into the state. That first year, it issued only 12 tags. The quota has slowly increased and now ranges from 600 to 1,500 tags depending on the year. For fall 2020, 98,000 people applied for 600 licenses.

The reason for so few elk tags compared to so many people who would like to hunt them is maintaining or growing herd size. All eastern states with elk are grappling with huge hunting demand for a limited number of elk licenses, if they have a season at all. The trick for state biologists is to limit the number and sex of the elk harvested to the point that, worst case, the population remains stable, and best case, it grows.

One of Kentucky’s challenges is keeping its elk where hunters have access to them. With 93 percent private land, the state leases hunting rights for the public from landowners. What’s more, Kentucky allows hunters to bait deer but not elk, so hunters are understandably upset when elk eat the corn set out to attract deer.

Pennsylvania also enacted its first elk hunting season in 2001. In the fall of 2020, 78,000 hunters applied, but the state only issued 164 tags, of which only 36 were for bulls. “We have massive bulls,” says Banfield. “The average age is six, and some are eight to nine years old. Lots of hunters covet this opportunity.”

Tennessee has had a limited elk season since 2009, selling only 15 permits per year of which seven are for archery, one is for a youth hunter and the remaining seven are for gun hunters. Starting three years ago, the state set aside one of the firearm tags for a raffle by a nonprofit partner, the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Foundation. The proceeds help fund conservation efforts in the state. In 2020, the raffle program raised $1.2 million.

Wisconsin also reserves one of its 10 annual elk tags as a fundraiser, through the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, for habitat and other elk management needs.

Elk have been successfully introduced in several eastern states.

Elk have been successfully introduced in several eastern states.

Elk Watching

The non-consumptive benefits of an elk herd are another big reason why some states decided to reintroduce them. Maggie Valley, North Carolina, on the edge of GSMNP, attracts thousands of elk-watchers each year. “There are viewing opportunities in town, though it’s not an ideal landscape, houses and elk, but you can see 800-pound elk close by,” says McVey.

Miller echoes the importance of elk-watching in Tennessee. “It’s huge,” he says. “We have 200,000 acres of public land where tourists and locals can see elk. We have elk-viewing towers which attract 15,000 visitors per year. It adds $10 million annually to the local economy.”

Elk watching has also boomed in Wisconsin, which brings in thousands of dollars to depressed communities. “Tourism is certainly appreciated by local residents, whether they hunt or not,” says Roepke.

Impact on Ecosystems

Given their enormous size, it’s easy to imagine the impact elk might have when placed in an environment that is no longer used to having them around. One common concern is elk out-competing white-tailed deer because elk are so much bigger, but that has not proven to be the case.

“Elk belong here,” says Jeremy Banfield, wildlife biologist with the Pennsylvania Game Commission. “It’s always going to be habitat dependent…Elk are not zoo animals granted parole.”

“The elk in Pennsylvania are eastern deciduous elk now, part of the ecosystem,” explains Banfield. “Elk and white-tails share the same space well. They have different niches. Elk are mainly grazers unless the snow gets too deep, but Pennsylvania winters are typically not severe. White-tails browse.”

Miller, in Tennessee, is also not concerned about elk adversely affecting their new home. “Elk are generalists,” he says. “They eat grasses for which white-tails have a low preference… In addition to grasses, elk eat Japanese honeysuckle, which helps control that invasive species. We focus on improving habitat to hold as many elk as we can on public lands and to increase the connectivity of those public lands so elk can move into new areas.”

Next Challenge: Managing the Herds

Perhaps the biggest challenge facing reintroduced elk, like other species, is the increase in human population. State conservation agencies place a high priority on preventing as many conflicts as possible, starting with careful consideration of the location for each reintroduction to avoid agriculture and highways. While incidents happen, they are uncommon and are greatly overshadowed by the opportunities for wildlife watching and hunting.

At this point, eastern states with elk have moved out of the restoration phase and into the management phase of having a herd. They continue to grow their elk numbers as habitat allows and to expand hunting opportunities based on herd size.

“Elk belong here,” says Banfield. “I would like to see their populations and distribution increase, but it needs to be balanced with the social aspects. It’s always going to be habitat dependent… Elk are not zoo animals granted parole. It’s okay to have more elk if they maintain their wild instincts and we still value them."

Elk across America are threatened by Chronic Wasting Disease. This always-fatal infection is now found in 29 states and three Canadian provinces. You can help secure funding for research and management of CWD.

Take action now