Editor’s note: This is the second in a series of short articles about various aspects of climate change. No single article is designed to address this topic in its totality nor is “Outdoor America” attempting to cover every conceivable climate-related issue. The goals of the series are to communicate the fundamental facts and address issues most relevant to the League’s mission.

Climate Change Affects Us All

In July 2019, a bus filled with 29 young Ikes rolled back into the hotel parking lot at the end of a long and exciting Izaak Walton League Youth Convention, held in Des Moines, Iowa. Except it wasn’t really the end of convention. The temperature in Des Moines had risen to 117 degrees that afternoon, and convention organizers decided it wasn’t safe for the kids to be out any longer.

That wasn’t the only impact extreme weather had on the youngest convention attendees. Just that morning, the newly elected youth leadership had devoted a slide of their presentation to describing the powerful thunderstorm that had disrupted their itinerary two days earlier. That same storm temporarily disabled an elevator and flooded a meeting room at the convention hotel.

In the end, these weather events resulted in some minor inconveniences and a memorable story to tell the Ikes back home. But, as intense storms and soaring temperatures become more common across the United States, the consequences can be much more severe.

Heat

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), heat is the number one weather-related killer. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reports that more than 8,000 Americans died from heat between 1999 and 2010.

Weather-related fatalities and injury statistics. (Click for larger version.)

Weather-related fatalities and injury statistics. (Click for larger version.)

Clearly extreme temperatures are hazardous to our health. And they aren’t likely to go away any time soon. NOAA reports that average annual temperatures in the upper Midwest region are now three degrees hotter than they were in the first half of the 1900s, with the rising trend driven by the increasing frequency of abnormally hot years.

Even when temperatures aren’t quite as extreme as they were in Des Moines last summer, other factors put us at risk of harm from heat. More than half of the U.S. population now lives in cities. Cities generally experience higher temperatures than surrounding regions due to having more heat-absorbing surfaces and more heat generated by human energy consumption. That exposes many of us to higher temperatures than what our rural cousins experience and the effect is amplified during heat waves.

Moreover, according to Gene Takle, a retired Iowa State University climate scientist, nights are warming faster than days in Iowa and many other places. That can lead to lost sleep and denies us a period of relief from sizzling temperatures, leaving us more vulnerable when the temperature rises again the next day.

Children are more at risk from heat because their smaller size provides less insulation between their core body temperature and the outside world. According to the 2019 Report of the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change, older people are also more easily affected by extreme heat, especially if they have underlying health conditions like diabetes or cardiovascular disease. While some of us may spend much of our time in air-conditioned comfort, others who need to be outdoors – either for work or recreation – face greater danger on the hottest days.

Flooding

Warmer air holds more moisture than colder air, which is why summers tend to be more humid than winters. When there’s more moisture in the air, more precipitation is likely. More precipitation, especially when it comes in heavy bursts, increases the likelihood of flooding.

As the climate changes, this pattern – more heat, more moisture, more precipitation, more flooding – is becoming a new status quo in some regions. Residents of the Missouri River basin have been experiencing this first-hand.

Following an exceptionally wet year in 2018, the 10 states along the Missouri River kicked off 2019 by being hammered by two major winter storms in just a couple of weeks. The first of those storms killed six people and caused billions of dollars in damage. The second storm dumped more than two feet of wet snow on the same area, resulting in runoff into the Missouri River nearly four times the average amount.

The situation only got worse from there. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (the Corps), which collects and reports runoff data for the river basin, kept raising its estimate of how much water would come into the Missouri by the end of the year. Starting from an initial prediction of “just slightly more than average,” the Corps changed its official forecast to 170 percent of the annual average, then 200 percent, then 238 percent.

Spencer Dam in Nebraska, before and after being damaged by one of the 2019 winter storms.

Spencer Dam in Nebraska, before and after being damaged by one of the 2019 winter storms.

By September, parts of the region had received as much as seven times its average seasonal rainfall. By October, the region smashed the record for the numbers of days the Missouri River had been above flood stage, surpassing the historic flooding of 2011. “Hundreds of people have been out of their homes, businesses, and farms since March,” Paul Lepisto, the League’s Regional Conservation Coordinator, reminded us in November, “and many properties have been destroyed.”

In January 2020, the Corps reported that actual runoff in 2019 had been 241 percent of the average. Nebraska and South Dakota recorded their rainiest 12 months ever, while the 10-state basin as a whole wrapped up the wettest three-year span in recorded history. The lower reaches of the Missouri River alone had racked up more than $3 billion in damage caused by the flooding.

Even though the flooding was declared officially over in mid-December, after a record 279 days, communities throughout the region remain vulnerable. A quarter of the levees along the river were damaged; repairs are likely to cost over $1 billion and last into 2021. The Missouri River reservoir system currently has more storage capacity than it did a year ago, but forecasters caution that heavy precipitation could cause flooding to begin again, especially in the lower basin states of Iowa, Nebraska, Kansas and Missouri.

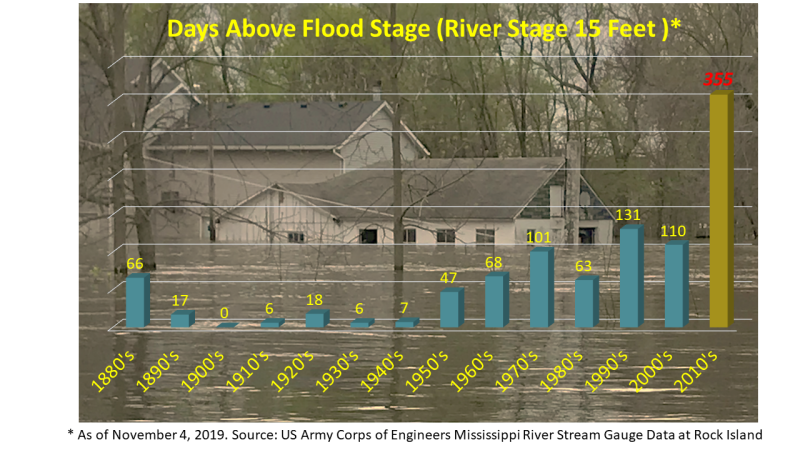

This shift isn’t affecting only the Missouri River region. The Great Lakes region now has 13.6 percent more annual precipitation than it did in 1951, according to the Great Lakes Integrated Sciences and Assessments Program (a partnership between the University of Michigan, Michigan State University and NOAA). As reported in the “Chicago Tribune,” this increasingly heavy precipitation poured an additional 56 trillion gallons of water into Lake Michigan between 2013 and 2019, raising the level of this massive inland sea by nearly six feet. According to data from the Corps, flood conditions are becoming much more common along the Mississippi River as well: In the 2010s, the river logged 355 days above flood stage, more than twice the total for any other decade in the past century.

Days above flood stage are increasing along the Mississippi River.

Days above flood stage are increasing along the Mississippi River.

Taxpayers Foot the Bill

As we look across more areas of the country, the damage caused by climate change – and the cost of that damage – continues to mount. According to CityLab, the federal government (or, really, the American taxpayer) spent over $100 billion on response and recovery after Hurricane Katrina barreled into the Gulf Coast. We collectively paid another $48 billion to repair the widespread damage caused by Hurricane Sandy, which battered the East Coast in 2012. NOAA concluded Sandy left behind an additional $18.75 billion in damage to property covered by private insurance, not counting damage that fell under the federally subsidized National Flood Insurance Program.

Disasters fueled by climate change are becoming both more expensive and more common. As climate.gov documents, the U.S. has experienced 241 billion-dollar disasters since 1980, with 45 of those occurring between 2016 and 2018. On average, disasters that cost at least $1 billion individually added up to $42.8 billion per year from 1980 to 2018. However, in the last five years of that period (2014-2018), the annual average was nearly $100 billion.

In 2018, Tyndall AFB in Panama City, FL, was leveled by Hurricane Michael.

In 2018, Tyndall AFB in Panama City, FL, was leveled by Hurricane Michael.

In 2018, we spent those dollars recovering from hailstorms in the Rockies, tornadoes in the central plains, winter storms in the Northeast, and several extremely destructive hurricanes in the Southeast. In the fall of that year, Hurricane Florence struck U.S. Marine Corps base Camp Lejeune in North Carolina, causing $3.6 billion worth of damage. Just a few weeks later, Hurricane Michael damaged or destroyed every single building on Tyndall Air Force Base in Florida, leaving behind a repair bill for another $3 billion.

What makes matters even worse is that the Department of Defense (DOD), which owns the two bases, was not an unsuspecting victim of these disasters: For years, DOD has been warning that climate change is a national security threat.

Our Work

Climate change could undo much of the League’s hard work to connect people to the outdoors and protect our air, water and other natural resources. On one day in September 2019, League members helped people build more than 350 birdfeeders out of recycled materials at the Iowa Outdoor Expo. The next day, they helped almost no one, as extraordinarily heavy rains washed out the popular annual event.

Last year’s persistent heavy rains in South Dakota washed huge quantities of trash into the Missouri River, while making it challenging for the League and partners to hold river clean-up events. Recreation on the river was affected too because high levels on the Missouri and its tributaries limited access for boaters and forced people to observe no-wake restrictions when they could get on the water.

Moreover, according to the National Climate Assessment – a major, Congressionally mandated scientific synthesis of climate impacts and trends across the U.S. – even if we continue to make progress on reducing nutrient pollution in streams and lakes, toxic algal blooms could continue to thrive, due to the warmer temperatures and heavier rainfall driven by climate change.

Climate change is resulting in costly damage to our infrastructure, harming our health, and threatening the natural resources and outdoor opportunities we treasure. In the next issue of “Outdoor America,” we’ll look at a range of policy responses, including improving soil health, reducing nitrogen fertilizer and use, and boosting energy efficiency that are supported by existing League conservation policy.

Learn more about climate science