Given the period, it was probably a smoke-filled room. Given the eight people present at the table — writers and reporters — no doubt the discussion was lubricated with liquor. But given the organization whose banquet they were attending, there’s also no doubt that all were concerned conservationists.

It was April 9, 1927. The location: Chicago, Illinois. A mile west of Lake Michigan and two blocks south of the Chicago River, the national convention of the Izaak Walton League of America was being held at the largest hotel west of New York — the grandly beautiful Hotel Sherman. Located at the northwest corner of Clark and Randolph Streets (now the site of the James R. Thompson Center), the hotel boasted 1,700 rooms with “Every Room Smart and Modern.”

The Hotel Sherman was the center of night life in Chicago. Celebrities, high society, and tourists flocked to its College Inn restaurant, an important fixture in Chicago’s growing jazz scene. There, amid the refined surroundings of the Hotel Sherman, jazz found its way into the center of society. The exotic Panther and Malaya rooms offered live music, dancing, and waiters dressed in Hindu outfits serving grilled meats on giant flaming sword skewers. Leopard skin-like fabrics, green palm leaves, panther sculptures, and lots of bamboo completed the mirage. For a 50¢ cover charge ($1.00 after 9pm on weekends) you could enter this mysterious world and, amid the pulsing jazz, order a “De Luxe Dinner” for $2.00.

An Idea Born

I have no idea if the seven men and one woman who were at the table later visited the exotic jazz rooms of the Sherman. But if they were like the outdoor writers I know today, it would be highly unusual if they hadn’t. For outdoor writers they were.

Just like the other Ikes gathered at the convention, these people were there to support the cause of conservation. At the time, the Izaak Walton League of America was by far the largest and fastest growing conservation group in the nation — which meant the world, since America was the leader in this movement. It is no wonder then that those who wrote about hunting, fishing, and the outdoors were ardent supporters of the Ikes.

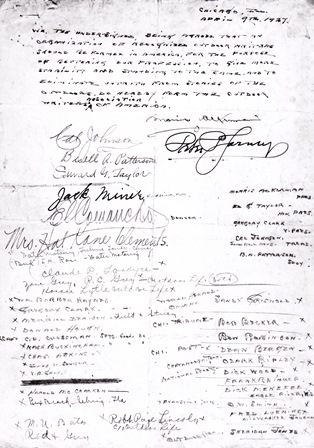

But this small group had yet another interest: To improve the quality and accuracy of outdoor writing and reporting. And so, on the back of the IWLA dinner menu, those gathered down and ratified these words:

Bill of Organization

Bill of Organization

“We the undersigned, being agreed that an organization of recognized outdoor writers should be formed in America, for the purpose of bettering our profession, to give more stability and standing to the same, and to eliminate untruths from stories of the outdoors, do hereby form the Outdoor Writers Association of America.”

Morris Ackerman, outdoor editor of the

Cleveland Daily News, wrote down those words and signed them with a flourish. The menu containing this new mission was passed around and signed by the others: Peter P. Carney, Cal Johnson (managing editor of the

Sporting Goods Journal of New York City), Buell A. Patterson of the

Chicago Herald- Examiner, Ed G. Taylor of the

Chicago Tribune, Jack Miner (founder of the Jack Miner Migratory Bird Sanctuary at Kingsville, Ontario), “El Comancho” (pen name of W.S. Phillips), and Mrs. Hal Kane Clements, identified as being with

Water Motoring, Tribune Tower, Chicago.

They jotted down on the same document a list of those they hoped to recruit, and soon many others — including the League’s first conservation director, Seth Gordon, and the famous writer Nash Buckingham — became charter members of the Outdoor Writers Association of America (OWAA).

“Outdoor writers who had won their spurs through experience,” wrote OWAA secretary James Stauber in 1938, “were griped by the counterfeit and the phoney and the bunkum which crept into the so-called outdoor columns and magazines as well. The reading public was being duped by the ‘pickers,’ ‘quack writers,’ and ‘clip artists’ who had ‘never been there.’ The result was the creation of the Outdoor Writers Association of America to purge the field and stream coverage of its ‘nature-faking,’ setting a higher standard in the outdoor writing game. If you read a newspaper whose columnist is a member of OWAA, you are reading the work of a recognized writer.”

Conservation Connection

The connection between the Izaak Walton League and the Outdoor Writers Association of America did not end with that 1927 banquet. Bud Ross, editor of the League’s Outdoor America magazine, joined OWAA. Not long after, one of OWAA’s founders, Cal Johnson, took over as Outdoor America’s editor. Johnny Mock, an OWAA charter member and outdoor editor of the Pittsburgh Press for more than two decades, actually began his writing career in 1924 by penning information for the newly formed Allegheny Chapter of IWLA. In 1939, Mock became the OWAA president. And for several years after the formation of OWAA, the group’s annual meeting was held at the League’s annual convention.

Since that time, the League has had a presence at nearly every OWAA national conference. Two former IWLA executive directors, Jack Lorenz and Paul Hansen, were not only outdoor writers in their own rights but also received OWAA’s top conservation honor, the Jade of Chiefs Award. And the current OWAA executive director, Tom Sadler, was IWLA’s conservation director. Considering that Seth Gordon, the Ike’s first conservation director, was a charter member of OWAA, it seems more than fitting that Sadler, having held that same League position, now serves OWAA.

Mutual Benefit

The mutually beneficial relationship among the outdoor media and conservation organizations is no less important today than it was when those eight OWAA founders sat in the Hotel Sherman. “The media and its role in public education are critical — a top priority — for advancing every conservation issue,” says Paul Hansen. “I don’t think it is an exaggeration to say that progress is made or missed by how well an issue is communicated and understood and by how well that information is used.”

The mutually beneficial relationship among the outdoor media and conservation organizations is no less important today than it was when those eight OWAA founders sat in the Hotel Sherman. “The media and its role in public education are critical — a top priority — for advancing every conservation issue,” says Paul Hansen. “I don’t think it is an exaggeration to say that progress is made or missed by how well an issue is communicated and understood and by how well that information is used.”

Hansen recounted an example of how the Ikes, working with the media, made a big difference. “In 1982, IWLA executive director Jack Lorenz had just hired a young, part-time guy to work on the issue of acid rain and arranged for a session at the OWAA annual meeting in Wichita, Kansas. I was that young guy, at my first OWAA meeting. I knew the issue cold, so Jack let me give the talk while he ran the slide projector. There were 400 writers in the room. Scores of articles resulted in the next year, hundreds in the next decade. This included virtually every outdoor publication and most major newspapers. It took another eight years, but compromise legislation passed in 1990. It would not have happened without the awareness in the hunting and fishing public.”

The Sherman Hotel and its exotic nightlife are gone. But the reason the Ikes met there has not changed, and the mission of the outdoor writers organization that was formed there is as important as ever.

“Outdoor communicators are the eyes and ears for the general public when it comes to things that affect soil, air, woods, waters, and wildlife,” says Tom Sadler. “They report and document the good and the bad happening to our natural resources from the ground level and do it from a position of appreciation for the resources and our outdoor heritage. Think of them as war correspondents for the conservation communities’ ground forces. Without them, the public will lose their connection to the natural world beyond their backyards and the work of the League and other conservation and outdoor recreation groups will be that much harder.”

“I bemoan the shoddy journalism we all see, the race to the lowest common denominator,” Sadler continues. “That’s why OWAA is still important. The phenomenal educational experience of our annual conferences is not duplicated anywhere, nor are the services provided by our staff and publications. Our first and most important role is to create the opportunity for our members to improve their skills and so improve the reporting on nature, the environment, and our enjoyment of it.”

The Ikes’ role, he said, and that of other conservation groups is to gather the science, do the field work, outline the debate, then deliver that information in digestible form to the outdoor press. The media gets its stories. The conservation groups get their message across. The public, hopefully, gets involved. In the end, the environment is healthier and fish and wildlife more abundant.

“Let’s face it,” says Sadler. “Without clean water, there won’t be anything to fish for. Without healthy habitats, there’s nothing to hunt, no birds to watch, no reason to go afield. And no need for outdoor writers, either.”

No doubt, could the OWAA founders who gathered at the Sherman Hotel read those words, they’d nod in wise affirmation.